29 Jan Why Do We Value Capital Efficiency?

By Carey Lai

With the Federal Funds rate having gone from 0% in February 2022 to 5.25% today, gone are the days when capital no longer has a cost. In an elevated interest rate environment, VCs and CEOs alike have now shifted from a “growth at all costs” strategy to more “capital efficient” growth. At Conductive Ventures, we invest in capital efficient, non-traditional entrepreneurs. We have done so since we were founded back in 2017 and we still continue to believe that backing and building capital efficient companies is not only good for us, it’s also good for our Limited Partners, our founders and CEOs, and their employees. While many venture capital firms formerly embraced a growth at all costs model, why is it that we have always valued capital efficiency so much?

I like illustrating what it means to be capital efficient with a story. Back during the dot-com era, my buddy Brad was given a seemingly impossible test by his boss – to get a Xerox machine, but without spending a single dollar to do so. Not sure what to do, Brad called the first company willing to lease him a Xerox machine and it turns out that the first month was free. 30 days later, his boss noticed that the Xerox machine was then switched out with another. When he asked Brad why the Xerox machine was being switched out, Brad explained that since he wasn’t given any budget, he discovered that he could leverage 30 day free trials from multiple companies in order to get free Xerox machines for the office. I love that story. It demonstrates creativity, resourcefulness and capital efficiency all at the same time.

Similarly, when my parents immigrated to the USA in the late sixties, all they had was a one-way ticket from Taiwan, and one piece of luggage. They were forced to stretch each dollar because money was a scarce resource, and they did so in the way they lived and raised us.

It’s how we at Conductive also run our firm. We encourage each team member to treat each dollar they spend at the firm like it’s their own, and to find creative ways for each dollar to go further. We have plenty of stories, similar to my buddy Brad, we’re happy to share.

Just as my immigrant parents creatively found ways to maximize each of their hard-earned dollars, just like Brad, my buddy, did, with the Xerox machines, and just like we do in running our firm, we like to think the best entrepreneurs also do so. That is why we think it is so important for us to invest in entrepreneurs who value capital efficiency, just like we do.

Source: Image generated by Dall-E

So, now that I’ve defined what capital efficiency is, allow me to convince you with three reasons why I think it’s also a much superior way to build successful companies:

-

- Sustainable, capital efficient growth makes money in the long run

- The pitfalls of T2D3 for SaaS companies

- When VC math doesn’t work for the entrepreneur

(1) Sustainable, capital efficient growth makes money in the long run

I always tell entrepreneurs that raising capital is a means to an end, not the end in itself. VCs won’t give you (at least I won’t) high fives for raising tons of capital and getting your company featured in TechCrunch. The best way to think about raising capital is a series of on-ramps and off-ramps to get you to your ultimate destination – a good M&A exit or IPO. Each time you raise capital, you’ve pushed the off-ramp that much further out. In fact, the off-ramp may get pushed out so much further that you, the entrepreneur, might make the same amount of money or none at all when all is said and done, but more on that later. If you only remember one thing, remember this: The more sensible rounds of capital you raise, the more you preserve your optionality. Since the majority of VC rounds are generally milestone-based financing, meaning you raise capital, build, build, build and then raise more capital. When you raise a ton of capital at really high prices, your set of potential acquirers shrink, and the larger and larger you get, the potential set of acquirers continues to shrink further and further. At the same time, your liquidation preferences will also continue to increase, to a point where the portion that you and your employees end up with could even be zero. As my finance professor once said about raising debt, but it also applies to equity, it’s like drinking wine with dinner. Perhaps there are benefits to drinking one or two glasses at dinner, but when you start drinking one or two bottles that is where you start to have problems. More is not necessarily merrier.

Lastly, when you raise a lot of money at once, generally two things happen: (1) You have increased pressure to deploy that capital in order to achieve higher growth expectations, even if you may not have really achieved product-market fit, and (2) You begin to develop a God complex where you think every project you start will be successful, because you have the capital to back it up. I’m here to tell you that the greatest weapon that a start-up has over a large publicly traded corporation is speed and focus. Big companies with big balance sheets are really good at spreading capital around internally, and funding all kinds of wacky projects with the understanding that few of them will ever pan out and that is OK for them. But start-ups on the other hand, don’t have that kind of luxury. In general, startups win because they do one thing extraordinarily well, and better than anyone else.

Source: Image generated by Dall-E

(2) The pitfalls of T2D3

First, what is T2D3? This is a growth metric for SaaS companies that stands for triple, triple, double, double, double. For example, growing from $2M in ARR to $6M, next year, to $18M to $36M to $72M and then to $144M in five years. With a 10x valuation multiple you now have a company worth in excess of $1B. I absolutely hate, hate, hate this metric. Why? Ever since this became the “gold standard” for what entrepreneurs thought SaaS VCs all wanted in 2021, what do you think happened? You guessed it. Every single SaaS company that pitched Conductive Ventures magically had top lines that went from $1M to $3M to $9M…or $5M to $15M to $45M…you get the idea. Yet, very few software companies are ever able to achieve this type of growth. In my completely non-scientific methodology, I think less than 1% of companies are ever able to achieve this type of growth. While I think this metric is very attractive in an excel spreadsheet, it completely ignores the challenges that come with it. I say this having invested in a company that has achieved T2D3 and eventually went IPO.

One of the biggest challenges of this model assumes that you have already obtained clear Product-Market Fit (PMF). All too often, what I see with many software companies that think they can achieve this type of growth is that they start spending lots of money to build out a sales organization without first defining their Ideal Customer Profile (ICP). Or, they are still in the process of figuring out their PMF. What I see often happening is a distinct increase in expenses without the commensurate increase in revenues or ARR. That type of scenario will often set you up for significant challenges.

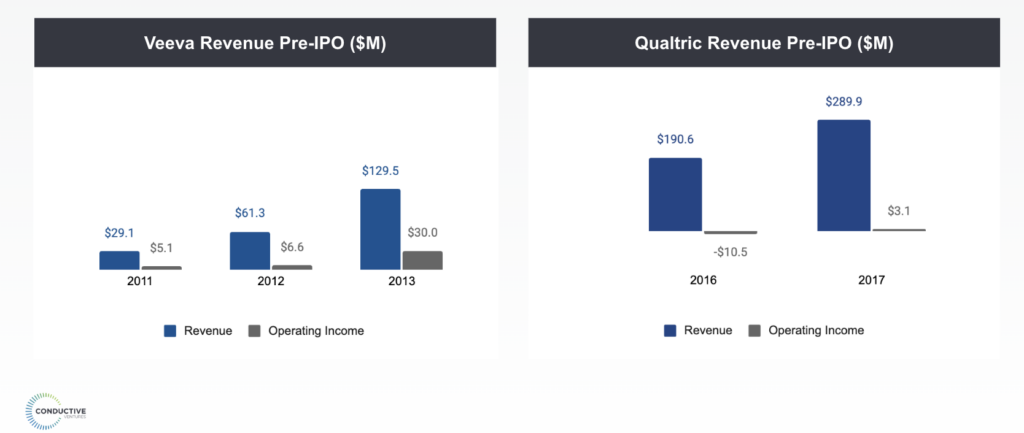

By the way, companies can do very well by raising very little capital, while honing in on the process of first clearly defining PMF and ICP. In fact, a company that does that well will find that they spend much less time having to redo stuff later. Two clear, shining examples of this in SaaS are Veeva and Qualtrics.

Veeva Systems, today a $33B market cap company, only raised $7M in its entire history before it went public in 2013. Founded in 2007 by Peter Gassner as an enterprise cloud provider to the life sciences industry, Veeva started as a single CRM product for a single industry. Veeva was one of the early examples of Vertical SaaS successes, as it chose to focus purely on its ICP in the life sciences industry to scale, and it did so with such capital efficiency. Gassner only raised two rounds, an angel round of $3M in 2007 from angel investors, and a year later, it raised a $4M round from institutional investors like Emergence Capital. No further venture capital was raised!

Today you would be hard-pressed to find another company going public on $7M of funding in under 6 years, but Veeva was a trailblazer. By 2013, it had $130M in annual revenue, up from just $13M in 2010 and had been breakeven in 2010 and profitable in the subsequent years. Its initial investor, Emergence Capital, made a 300x return on its $4M investment in 2008!

Source: Photo by Ben Hider/NYSE Euronext

Qualtrics, an experience management software company, was founded in 2002 by brothers Ryan and Jared Smith alongside their father in the basement of the family home in Provo, Utah. Unlike most startups, the founders bootstrapped the company for almost a decade, until 2012, when Accel led the first outside investment, raising a massive $70M Series A round. Taking the long road to financing, by being capital efficient, getting to PMF, and focusing on scaling the company in a focused manner, Qualtrics built the company on really solid footing, and set a path to profitability very early on.

It’s why, by the time they were planning to IPO just 5 years later in 2017, Qualtrics’ revenue had surged from ~$50M in 2012 to $290M in revenue in 2017 with nearly 75% gross margins. Given that strong footing, SAP made an $8B acquisition offer for Qualtrics in 2018 which the founders accepted. Qualtrics has since been spun out of SAP and listed publicly, then re-acquired by SAP and re-divested once more. It is currently owned by PE funds, and has raised $3.22B in total funding through its life. But remember, for the first 10 years, it was completely bootstrapped.

(3) When VC math doesn’t work for the entrepreneur

What’s VC math? It’s the math that makes the business model for VCs work. What do I mean? VCs make money in two ways: management fees and carried interest. Both are based on the percentage of the fund’s size. So, in essence, there’s a perverse incentive for a fund to raise as much capital as possible in order to make more management fees. In a way, this can work against carried interest because the more money you raise, the more challenging it will be to return capital. Let’s assume a 2.0% management fee per year for 10-years for a $100M fund – that would equate to $20M in management fees over the lifetime of a fund. Now, let’s assume a $1B fund, that would equate to $200M in fees. Get the idea?

Now, if companies are too capital efficient, that means that they won’t consume as much capital, which means VCs won’t be able to raise bigger and bigger funds. So, perhaps there’s also a perverse incentive on the VCs’ part to ensure that companies are not too capital efficient.

On the other side of the VC math equation is the entrepreneur. Let’s say a CEO raises a sensible Series A of $15M and after the round the CEO now owns 25% of his company. If the company were to be sold the next day for $300M, the CEO would earn $75M ($300M x 25%). Now, let’s say instead, a year later, the CEO decides to raise a $50M Series B and gets diluted to 15% ownership, how much would he now have to sell the company for, to earn the same $75M? If you said $500M, you’re correct (15% x $500M=$75M). This gets back to my first point, that capital raises are a series of on-ramps and off-ramps to your M&A exit or IPO opportunity. Every time you raise capital, the next series of investors will expect/underwrite a certain amount in return. Each time you do so, due to dilution, the exit needs to be that much bigger in order for you to earn the same return as a CEO. So, before you raise capital, you really need to think about the potential exit, your total liquidation preference post exit and what potential optionality you preserve.

Lastly, keep in mind that at the end of the day, the VC diversifies risk by creating a portfolio of investments. Some of those investments may do great while others may not. I think the way to increase the chances of ensuring that more companies do well in a portfolio vs. fail is to have as many capital efficient businesses in the portfolio.

As an entrepreneur, you want to make sure that you’re not stuck having to pay the bill when everyone else is out popping champagne bottles. The reason why capital efficiency is a winning strategy for all involved: it preserves exit optionality for CEOs, sets the company up for sustainable long-term growth, and ensures that when all is said and done, everyone around the table walks away with more than they started with. Now isn’t that something we can all get behind?

If you are building a capital efficient business, reach out to us at info@conductive.vc. If not, we’ll refer you to other VC firms who don’t care about capital efficiency. =)

With additional contributions from Robin Chan